Critical Internet literacy and teleological epistemology: where are we heading?

A blog by Colin Harrison, University of Nottingham

A blog by Colin Harrison, University of Nottingham

Has the World Wide Web changed the nature of knowledge? Yes!

But if so, what are the implications for teachers?

If ‘knowledge’ is now an epistemological battleground, what weapons do we have? And can philosophy help us?

The demands of digital literacy are changing, as navigating the Internet and creating content become ever-more complex for both teachers and students. As the Internet has evolved, so the concepts of truth and of knowledge in relation to the Internet have evolved.

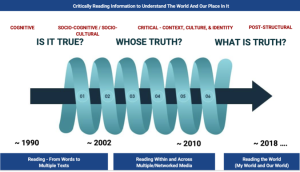

Julie Coiro’s diagram helpfully demonstrates some of these changes (Coiro, 2023). In 1990, Tim Berners-Lee set up the World Wide Web with the intention of creating a platform for the free and worldwide exchange of information, and this had profound epistemological implications. The nature of knowledge itself changed: instead of being owned by those who had books, knowledge was democratised, and could be found by anyone with access to the Internet.

But at the same time as knowledge was democratised, its authenticity was challenged. Instead of having knowledge that had been through many layers of filtration, and judged to be fit for publication by experts, we now have a publishing free-for-all, with anyone’s ‘knowledge’ published for 6 billion Internet users.

Wikipedia (April 2024) defined Knowledge as:

An awareness of facts, a familiarity with individuals and situations, or a practical skill. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional knowledge, is often characterized as true belief that is distinct from opinion or guesswork by virtue of justification.

However, every one of the highlighted terms is problematic, and they lead us to Julie Coiro’s question ‘WHOSE TRUTH?’.

But what is a ‘fact’? According to the traditional view of epistemology, ‘knowledge’ is ‘a belief that is true and justified’. So the key to differentiating knowledge from opinion of guesswork is ‘justification’. However, defining ‘justification’ is problematic: philosophers don’t agree. In other words, ‘WHOSE JUSTIFICATION?’ is part of the ‘WHOSE TRUTH?’ problem. Julie Coiro’s third epistemological stage asks ‘WHAT IS TRUTH?’, which bring us to the ‘post-structural’ era, in which “truth” is not a fixed concept, but instead constantly changes based on a person’s cultural, political, social, and economic position in the world.

This may seem an anarchic state of affairs, but we do not necessarily need to see the world as leading to an implied fourth stage of an information apocalypse. Teleology is the study of the final causes of things, and asks the question ‘what is the final purpose of this?’ We can pose this teleological question, and ask, ‘What is the ultimate goal of the World Wide Web?’. The philosopher Jane Friedman (2019) has used the phrase ‘teleological epistemology’ to refer to a belief that many of us have as teachers: namely that ‘knowledge’, in its widest sense, is our primary goal. And for many of us, critical Internet literacy is a vital tool in helping to achieve that goal.

‘Truth’ may be provisional, but we can offer a number of propositions whose ‘truth’ will be judged in the coming years, but which are at this point justified by what we have learned from research:

- Every user of the Internet needs to develop and apply critical digital literacy

- Critical digital literacy can be taught: students in elementary schools are perfectly capable of applying rules such as “Be alert! Be suspicious!”, “Read between the lines,” “Make late decisions,” “Integrate information across sources,” and “Make joint decisions”

- Students working in groups of three can learn critical digital literacy collaboratively

- Dialogue and uncertainty are the enemies of dogmatism and authoritarianism

- Artificial intelligence tools can be dangerous but they can also be incredibly valuable, for everyone

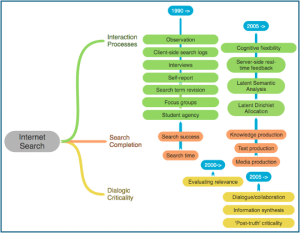

As the Internet has evolved, so pedagogy has evolved. The diagram below (Harrison, 2023) attempts to capture how researchers have sought to capture data on how students are using the Internet as they search for knowledge.

Research in the 1990s focused on search completion, but increasingly researchers have focused on users’ interaction processes and criticality, and with an increasingly wide lens. Although we have anxieties about people believing ‘fake news’, such a concern is predicated on the belief that there is ‘truth’ out there. Equally, the fact that our research now encompasses students as producers of knowledge reflects our trust that the democratisation of knowledge production is also possible. Knowledge production can help to develop identity and a sense of agency, and our students can become collaborators in constructing truth.

References

Coiro, J. (2023) Critically reading information to understand the world and our place in it: diverse perspectives and related challenges for research & practice. LRA conference, Atlanta.

Friedman, J. (2019) Teleological epistemology. Philosophical Studies, 176(3), 673-691.

Harrison C. (2018) Critical Internet Literacy: What Is It, and How Should We Teach It? Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy. Jan;61(4):461-4. 2

Harrison, C. (2023) Evaluating, supporting and enhancing Internet search activity: a review of research, with implications for pedagogy. In: Tierney, R.J., Rizvi, F., Erkican, K. (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Education. Elsevier.